Gloria Swanson was ready for her close-up. Dressed to the nines, she passed under a vine-covered stone archway and through the red "diva of the weekend" door, then swanned into the grand ballroom at Paradise Springs. It was May 1928 and the silent film actress was draped on the arm of her lover, film financier Joseph Kennedy Sr. The pair, both married to other people, had come to party with actor Noah Beery and a thousand or so of his closest friends at a luxe compound in the San Gabriel Mountains.

In the midst of Prohibition, these merrymakers drank, dined and danced the night away. They packed the venue, which boasted a high-beam ceiling, a hardwood dance floor, a 45-foot redwood bar and a stage large enough for a 22-piece orchestra. The scene was absurdly lavish but it was also fairly typical for a weekend at Paradise Springs, a debaucherous destination for early Hollywood's biggest stars.

Don't miss any of our quirky stories: Sign up for the LAist weekday newsletter >>

After Kennedy, father of future U.S. President John F. Kennedy, escorted Swanson to her seat, he heard a loud knock on the door. He assumed it was Jack Warner or Cecil B. DeMille, playing a prank. Enraged, Kennedy flung open the door and came face to face with a giant bison, which charged past him into the ballroom.

Pandemonium broke out. The confused animal slid across the dance floor, knocking over tables and chairs as celebrities in formal attire scrambled to get out of the way.

Beery's teenage son, Noah Beery Jr. (later of the Rockford Files fame), ran up the hill to his father's cabin and yelled, "Dad! There's a buffalo in the ballroom!" The elder Beery raced down to the ballroom, grabbed a shotgun, jumped onto the bar and shot the poor buffalo between its eyes. He then invited his rattled guests to return the following weekend for a free buffalo barbecue.

Beery Jr. said in a 1994 interview with Bill Hunt, marketing director for Big Rock Creek Camp (the Christian camp that later operated at Paradise Springs), that he believed the animal had been taken from the camp's zoo and stationed there by William Randolph Hearst's goons. The newspaper magnate had an ongoing feud with Noah and Wallace Beery. Beery Jr. told Hunt their beef began at least two years earlier, in 1923, when Swanson, who was married to Wallace Beery at the time, pushed Hearst's mistress, Marion Davies, into the pool at Paradise Springs.

In addition to hosting early Hollywood stars, Noah Beery brewed illegal booze and farmed trout for many years, but eventually the good times ran out. Decades after he went bankrupt and lost the property, Paradise Springs pivoted to become a Christian camp, in stark contrast to its racy past. In 2017, it was sold to a French glamping company. After a four-year revamp, Huttopia Paradise Springs opened August 13 touting its luxury yurts and communal outdoor activities.

A Hedonistic Wonderland For Early Hollywood

In 1910, prominent Pasadena lawyer Louis Luckel spent $200 to buy 165 acres of land in the Angeles National Forest, a parcel that Swanson later named Paradise Springs. Located about 65 miles northeast of L.A., the land had previously belonged to Caldwell Evans, a retired Pittsburgh doctor who owned 880 acres in the area.

Luckel "intended to sire seven sons, but ended up with only one nature-hating daughter," according to a 1999 story in Antelope Valley's Daily Press. Her name was Adelaide and she preferred genteel Pasadena society to the solitude and wilderness of the forest. She pushed her father to sell the property.

Noah Beery happened upon Paradise Springs while on a hunting trip in 1915. He took to it immediately.

At that point in his career, 33-year-old Noah had recently arrived in Los Angeles after spending 12 years as a stage actor on New York's vaudeville circuit. He had come to join his younger brother Wallace, then 30, who had parlayed a job as an assistant elephant trainer at the Ringling Bros. Circus into an acting career on Broadway, then in moving pictures.

The Beery brothers spent their early careers under contract to Paramount Studios and later to MGM. Noah typically played silent film villains, most famously in the Mark of Zorro, the Spoilers and Beau Geste.

Wallace, who had made his name playing a Swedish maid in drag in a series of comedic films, was cast as the heavy in such films as Patria, the Last of the Mohicans and Viva Villa. In 1931, he would win a Best Actor Oscar for The Champ, tying with Fredric March for Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (the only time the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences awarded a tie in that category.)

The Beery brothers had grown up on a Missouri farm. They fancied themselves rugged outdoorsmen. After pooling their resources and securing funds from other stars, including Charlie Chaplin, Will Rogers and Douglas Fairbanks, they made Luckel an offer for Paradise Springs. He accepted but, in a shrewd move, included a clause in the contract stipulating that if the Beerys declared bankruptcy, the property would revert to him.

The hard-partying actor brothers had a vision. They wanted to turn the place into a hedonistic playground for themselves, their famous friends and whoever else could afford the price of admission. Amid the majestic oaks and evergreens, the Beery brothers built the elegant ballroom along with 27 stone cabins, an Olympic-size swimming pool, tennis courts and 36 fish hatcheries with a series of rock and mortar ponds that they stocked with one million rainbow trout.

Beery built himself a cabin overlooking the cascading ponds of Paradise Springs. After a 1938 flood destroyed most of the property but left the cabin intact, it became known as Noah's Ark.

'Everything Was So Illegal'

The Beery brothers unveiled their A-list getaway around 1920. It didn't come cheap. A cottage for a single weekend would run you $250, nearly $4,000 in today's dollars.

Stars often arrived by limousine. In addition to Hearst, Davies, Chaplin, Kennedy, Swanson, Warner, Fairbanks and DeMille, the camp was frequented by Greta Garbo, Mae West, Mary Pickford, W.C. Fields and Johnny Weissmuller, among many others.

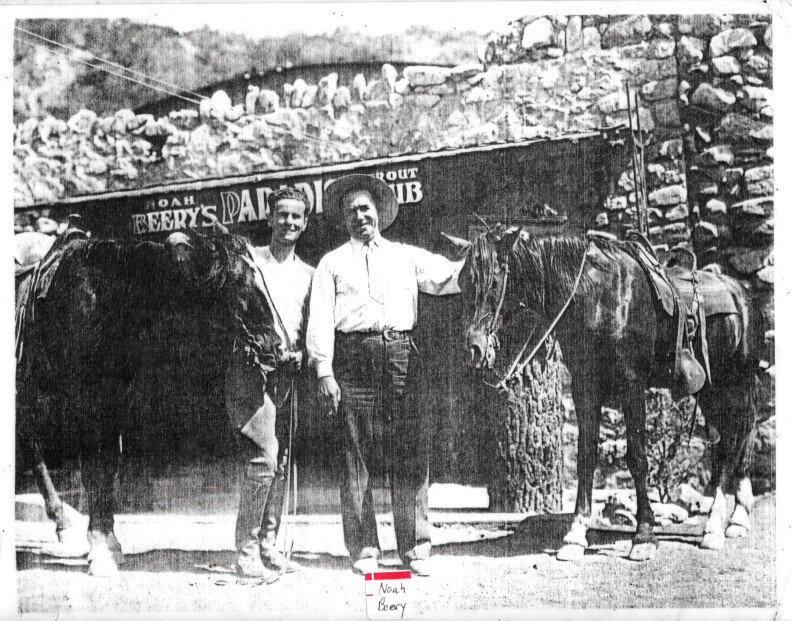

The Beerys threw wild parties, brewed illegal hooch, gambled, hosted tennis tournaments, operated a cathouse and raised trout, which Noah sold to the Brown Derby restaurant and the Cocoanut Grove nightclub back in Los Angeles. He called his operation the Noah Beery Paradise Trout Club.

Beery Jr. told Hunt in 1994 that no one would believe what went on at Paradise Springs during the 1920s and '30s.

"Everything was so illegal," Hunt says, describing the stories Beery Jr. had recounted. "There was bathtub gin, gambling and a slew of beautiful would-be 'starlets' ready to make the acquaintance of visiting studio executives."

Beery Jr. told Hunt how Charlie Chaplin, in 1923, had single-handedly built a rickety, winding staircase — still standing today — in his father's cabin. Chaplin used the stairs leading up to the second-floor bedroom for what Beery Jr. called his "extramarital romantic trysts." It was Beery Jr.'s job to warn Chaplin when his wife was coming up the hill so he and his mistress could escape out the back window.

"Chaplin loved Paradise Springs and invested heavily in its operations and events," Hunt says.

For a while, money was no object to the Beerys. They added a zoo with an elephant, kangaroos, buffalo and camels, much like the one their rival, Hearst, had at his San Simeon estate.

Unlike Paradise Springs, guests didn't have to pay to visit Hearst Castle but it was a couple hundred miles further away from Hollywood. So Hearst commissioned private passenger trains to ferry guests from Union Station to the central California coast every Friday afternoon and take them back to Los Angeles on Sundays.

"The week San Simeon opened [in 1919], two of Hearst's thugs allegedly tried to torch Paradise Springs. In all, Hearst tried nine times" to ruin Beery's paradise, according to Hunt.

In 1923, when Swanson pushed Davies into the pool at Paradise Springs, "Hearst got mad and almost shot Wallace Beery. Then, [Hearst] left in a huff, to [expand] San Simeon and dwarf Paradise Springs," Hunt says. Two years later, Hearst supposedly exacted his revenge, with some help from a buffalo.

Paradise Lost

In 2016, Jonathan Odell, a member of one of the four families that would later run Big Rock Creek Camp at Paradise Springs, found a 1927 letter at a San Diego rare book dealer from Noah Beery to Cecil B. DeMille. The existence and contents of the letter have not been previously reported.

In the letter, written on Paradise Trout Club letterhead, which included an illustration of Beery holding a fish over a mountain stream, Beery asks the film director to invest in his Trout Club. It reads, in part:

"I have had in my mind every day the fact that my initial roster could not be right in any sense of the word without having your name at the top or mighty close to the top of the page. I have set a privilege fee including initiation and a year's dues together with war tax at $105. I know that everybody concerned will be disappointed and I most of all if you are not one of the first few and I also know that you do not want any such general disappointment to exist, so come on in and be one of us.

I may be prejudiced as the father looking at his favorite child, but it does not seem to me that any language supplied by a paid writer could make clear the beauty, the joy and the wholesomeness that is made possible for us folks at this property."

We don't know if DeMille invested in the venture. Despite the Beery brothers' high-profile friendships, a series of events over the next decade led to the demise of Beery's paradise.

As "talkies" usurped silent films, a new wave of stars replaced the earlier generation of actors, including Noah and Wallace Beery. Although trout were still on the menu at the Brown Derby, they no longer came from Paradise Springs. The mountain water had proven too cold for trout propagation and the fishery failed.

In 1928, Noah Beery's wife filed for divorce. Two years later, a cook at the Trout Club sued him for $1,950 in damages for "rough treatment." According to the Los Angeles Times, Beery "struck [the cook] in the mouth and threw him forcibly out of the club building, compelling him to remain outside in the cold for five hours."

Also in 1930, vandals broke in and destroyed showcases, damaged cars and stole a truck along with $1,000 worth of food and cigarettes. Later that year, a mysterious fire destroyed the grand ballroom.

"Many believed Hearst had [the fire] started by some of his thugs because of an argument he had with Wallace," Hunt says.

In 1938, a historic, "50-year flood" barreled through Paradise Springs and washed out approximately 80% of the camp, including many of its buildings and trout ponds. Fish were left strewn around the canyon. The five-day storm wreaked havoc throughout Los Angeles County, causing $78 million in damage ($1.43 billion in 2020 dollars) and killing 115 people, according to the Los Angeles Times.

Beery's paradise had become a "financial, if not emotional, albatross," according to a 1988 Los Angeles magazine story.

Beery went bankrupt in 1940, triggering the clause in the 1915 sales contract that returned ownership of the property to Louis Luckel. To say that Beery, who had grand plans for a housing project and recreation center on the site, was unhappy about this turn of events is an understatement.

"Beery was very bitter, with an 'If I can't have it, no one can' attitude," Bob Anderson, resident of nearby Valyermo, told the Antelope Valley Press in 2005. "He tore down some cabins, rolled up fences, dynamited the ponds... It would have taken $1 million to get it back to the way it was."

While Beery continued to make more movies — nearly 200 in total over the course of his career — his box office appeal was fading. On April 1, 1946, he died of a heart attack in Beverly Hills at age 64. In his obituary, The New York Times wrote, "The veteran film actor died in the arms of his brother, Wallace Beery." Wallace died three years later, also at age 64.

'Good Neighbors'

No records indicate what Luckel did with the property during the 1940s but after he passed away in 1952, possession of Paradise Springs passed to his daughter, now Adelaide Pettijohn.

Over the next decade, she leased the property to a succession of entrepreneurs who tried, without much success, to recapture some of its glory as a resort.

In 1965, she challenged her nephew, Lawrence "Gunner" Payne, to "do something with the mountain property," Payne wrote in a history of the property in a pamphlet in the '80s. He decided to launch Paradise Springs Camp, a family-oriented campground and retreat center with a Christian emphasis, which ran from 1971 to 1981. The Christian camp's new rules forbade alcohol, gambling and dancing. Sunday services took the place of opulent shindigs. There were no party-crashing buffalo.

Perhaps Payne threw himself into the project as a way to overcome his grief. In the early 1960s, his 4-year-old daughter was kidnapped, raped and murdered by "one of the hired hands in the [Payne family's] orange grove orchard" in Yorba Linda, according to Wilma Odell, who served as camp director of Paradise Springs' Big Rock Creek Camp in the 1990s and early 2000s, and fellow preachers Andy Taylor and John Wimber.

Payne achieved moderate success operating the property but it was ultimately a drain on his and his aunt's resources. At one point, Adelaide almost foreclosed on the property because Payne was in arrears, "but she never did the foul deed," he wrote.

Paradise Springs Eternal

In 1981, Payne sold the campground to four families, including the Odells. They renamed it Big Rock Creek Camp and retained its Christian focus. For 35 years, they hosted anywhere from 150 to 500 people each weekend, most of them from church groups, totaling about 8,000 guests a year.

Lacking new investment, the four families decided in 2017 that it was time to move on. They considered selling the property to Nestlé, which was interested in the spring that generates 1 million gallons of water per day.

Instead, they sold Paradise Springs — now 144 acres after small portions of the original parcel were sold over the years — to Huttopia, a French glamping company founded by Philippe and Céline Bossanne. The four families liked Huttopia's plan to maintain Paradise Springs as a family-centric camp and invest money in upgrading the property.

"We trust that Huttopia will be good neighbors," says Jonathan Odell, whose family has held onto one acre.

Philippe Bossanne says Huttopia plans to highlight the unique history of Paradise Springs, including Charlie Chaplin's rickety staircase.

The company has removed the stone arches that Swanson, Kennedy and a buffalo waltzed under 96 years ago and it added luxury yurts. But Huttopia has maintained many of the existing structures, cabins and trout ponds as well as the kitchen, pool and other features from the Beery era. The new iteration of Paradise Springs reopened on August 13, with rooms going for $220 to $450 per night.

Margaux Bossanne, who manages Paradise Springs, says the company is working hard to deliver what the resort's name promises.

"There are no roads, no cars, no traffic, nothing," she says. "You're in the middle of nowhere with just the sound of the river and the birds. It's going to be very beautiful."

Huttopia Paradise Springs is located at 18101 Paradise Dr., Valyermo, CA 93563.