From Part 1 of This Special Report

Frank A. Clark, MD

Asian American Mental Health: Treating a Diverse Population at a Crossroads

Geoffrey Z. Liu, MD; Margaret Cheng Tuttle, MD

María José Lisotto, MD; Andrés Martin, MD, MPH

Women experience depression at rates twice that of men. But Black women are only half as likely to seek care as White women. Here's what you can do to help this population.

Studio Romantic/AdobeStock

SPECIAL REPORT: MINORITY MENTAL HEALTH PART 2

Black women face significant disparities in mental health care. Understanding why these differences occur requires an appreciation for not only the multiple roles that Black women play in society but also for the racial and social injustices they have historically faced. Notably, the outlook for Black women often depends on the perspective. Some mental health providers believe that they are some of the most disadvantaged people in the United States, often simultaneously experiencing racism, sexism, and, at times, financial inequality. Others believe that this same concept makes Black women one of the most resilient groups around. Both may be true in different settings; consequently, it is important to navigate these concepts carefully to understand the state of mental health of Black women and to optimize treatment outcomes.

Stigma in Disparities

Since women experience depression at rates twice that of men, society may expect the percentage of Black women receiving care to mirror that of White women. However, Black women are only about half as likely to seek care. Why these numbers are so different needs to be explored.

Historically, studies have shown that Black individuals are less likely to seek (and subsequently accept) mental health care, secondary to concerns regarding stigma.1,2 For example, Black women diagnosed with postpartum depression are less likely to accept medication recommendations and therapy.3 Although this difference in participation in care is often attributed to stigma, recent data show that stigma is not one of the main reasons that Black women do not seek help. Instead, their willingness to seek care often depends on their prior experiences with mental health treatment.4 Identifying barriers to care in a timely manner is important because, as depression severity increases, Black women become less likely to pursue care.5 One key component required to reduce disparities in participation in care is acknowledging that different messaging is required to form a therapeutic alliance with patients. This is not an issue unique to the United States. Similar issues in disparities of care exist for Black women living in other countries.6,7

Culturally Sensitive Care

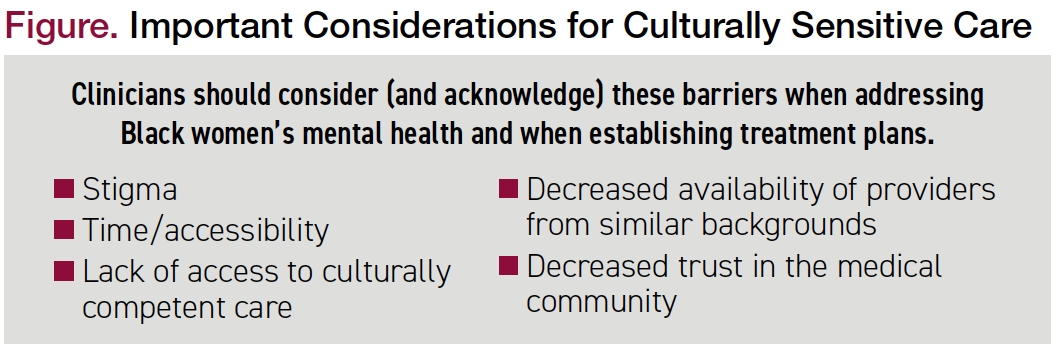

If stigma is not the limiting factor, what is creating barriers for Black women who require mental health interventions? It is important for psychiatrists to identify these barriers since acknowledging them will improve the physician-patient relationship when caring for Black women (Figure). One significant barrier is access to health care providers. According to the American Psychiatric Association, Black clinicians represent only about 2% of practicing psychiatrists and 4% of psychologists providing care. This disparity is further compounded in psychiatry subspecialty training programs such as substance abuse fellowships.8

Figure. Important Considerations for Culturally Sensitive Care

Black individuals are more likely than White individuals to receive diagnoses with poor long-term outcomes. For example, schizophrenia is more likely to be the diagnosis assigned to Black patients compared with their White counterparts when patients present with similar symptoms.9 Often the differential diagnosis for these patients is vast and includes unspecified psychotic disorder, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or schizoaffective disorder, to list a few possibilities. The messaging to the patient and their families, as well as the staff acutely caring for them, is important. Psychotic symptoms deemed secondary to schizophrenia often result in higher incidents of seclusion, restraints, and involuntary commitment.

Frank A. Clark, MD

Asian American Mental Health: Treating a Diverse Population at a Crossroads

Geoffrey Z. Liu, MD; Margaret Cheng Tuttle, MD

María José Lisotto, MD; Andrés Martin, MD, MPH

Case Study

“Lydia” is a Black woman, aged 35 years, with a prior psychiatric admission for depression following a relationship break- up while attending college. She was started on antidepressants, completed college, and subsequently discontinued her medications. Lydia remained euthymic until the COVID-19 pandemic, when she found herself at home with 2 children who were participating in virtual learning while her partner continued to work outside of the home. She frequently watched media coverage related to the murder of George Floyd and, at some point, began to believe that every time she heard any type of loud bang, the police were killing a Black man. This created such distress that she ultimately presented to the emergency department, not once but twice.

During Lydia’s first admission to inpatient psychiatry, her family was informed of a possible diagnosis of schizophrenia. She was discharged on an antipsychotic, but shortly thereafter Lydia again became acutely ill. She was subsequently admitted to a second hospital. There it was determined that she had severe anxiety, likely preceding what became a brief psychotic disorder.

Lydia was started on a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor and a second-generation antipsychotic, and her symptoms resolved. Weekly outpatient therapy was added to the treatment regimen, and she was followed in an outpatient clinic for the next year without recurrence of symptoms.

Like many Black female patients with mental health issues, Lydia saw a potential family member or close friend in George Floyd. In the aftermath of his murder, we as Black women feared for our own relatives, and it affected us in a way that people of most other races could not fully relate to. It is possible that the patient presented differently during her second 2020 admission. However, it is also possible that the discussion among the patient, her family, and the second treating physician—who also was a Black woman—allowed them to share more pertinent details about Lydia’s symptoms. A better understanding of potential underlying triggers for her presentation also provided hope regarding her overall prognosis.

The Patient Relationship

Challenges Facing American Indian and Alaska Native Patients

Roger Dale Walker, MD

This case study highlights the importance of culturally sensitive care. Black female providers are a small but powerful group. We have achieved great success, but many of us have felt additional weight, especially during the pandemic. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention surveys have indicated that rates of anxiety and depression increased in all age groups during the pandemic.10 Survey numbers also highlighted the increased mental health needs of Black women during this timeframe. Compound these psychosocial stressors with those magnified by the ongoing traumas experienced by the murder of George Floyd, and by countless other Black Americans victimized by unjust policing practices and structural racism, and the result often is that people of color seek clinicians who look like them and (presumably) share a common belief system.

This culturally sensitive care in a doctor-patient relationship is important and has an impact on care and outcomes in other disciplines beyond psychiatry, including pediatrics, obstetrics, and gynecology. For instance, the mortality rate for Black babies decreases by nearly 50% when cared for by doctors of the same race.11 Similarly, Black women are also 3 to 4 times more likely than White women to die from complications related to childbirth, a disparity that persists even when accounting for socioeconomic status.12 Presumably, increasing the number of Black obstetrician/gynecologists would decrease morbidity and mortality in this cohort.13 Although additional studies are needed to determine definitively if racial concordance between physician and patient plays a direct role in maternal outcomes, such concordance has been shown to influence patient-physician communication and perceptions of care, both of which are important factors in overall health outcomes.14

Of course, it is unrealistic to think that all Black patients will be suitably matched with clinicians with similar racial and cultural backgrounds. This means that we will need additional support. Although there may not be a shared historical perspective, it is imperative that all clinicians try to understand cultural differences. Race and culture are key components to how our patients relate to their doctors, but many other components are integral to providing culturally sensitive care. It is important not to presume to understand the lived experiences of patients. Instead, it may be necessary, at times, to admit a lack of insight. Simultaneously, it will be necessary to commit to learn more and combine this new knowledge with one’s current skillset in developing an appropriate treatment plan. These extra steps help identify cultural beliefs and leverage them in treatment interventions, which is extremely important.

Normalizing the Message

Black women, collectively, breathed a sigh of relief when the former first lady, Michelle Obama, spoke about having a low level of depression during the first few months of the pandemic. By revealing something that many women, especially Black women, have difficulty sharing, she made talking about mood more acceptable. She also validated what many other women were experiencing. Now that Mrs Obama and several other high-profile women have discussed their struggles with depression, it is imperative that we continue with the necessary work to change the narrative for women of color who are now ready to talk about mental health and pursue treatment.

Quite possibly, we will not fully understand treatments and interventions that are best for Black women until more research is performed. Lack of trust in clinical trials and, at times, in the entire health care system predate the examples that are often cited, including the Tuskegee Experiment and the harvesting of cells from Henrietta Lacks. To be clear, Black populations have been mistreated by the medical community for centuries. The question, now, is how do we earn the trust required to move forward with identifying diagnostic and treatment interventions that work best for minority populations?

Future Directions

What should mental health professionals do to support Black women’s mental health needs moving forward? The answer is multifaceted. We must first acknowledge that there is a need for cultural competency. Second, as providers, we must enhance our commitment to training a diverse workforce. We know that female and Black clinicians are historically underrepresented in the field. Although we anticipate ongoing increases in women becoming psychiatrists, there is a need to support the recruitment and subsequent mentorship of minorities in our field.

When caring for Black women, and Black men as well, remember that there is not a one-size-fits-all (or even one-size-fits-most) approach. It is important to have culturally sensitive members of your hospital, clinic, or outpatient practice who can help identify strategies for developing a therapeutic relationship and explain beliefs and cultural nuances. It is also imperative for organizations to understand the importance of employing a workforce with multiple team members who can contribute diversity of thought. Having a few providers or staff members of a different race (or gender) does not mean that a comprehensive treatment approach will be easy. Instead, we must continue to have tough conversations and engage in discussion related to cultural, racial, and ethnic differences. If providers take this approach toward caring for each of their patients, Black women will continue to pursue care that meets their needs in a culturally sensitive manner, thus increasing the likelihood of a successful outcome.

Dr Richards is the chair and medical director of the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Health at Sibley Memorial Hospital, as well as an assistant professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

References

1. Roberts KT, Robinson KM, Topp R, et al. Community perceptions of mental health needs in an underserved minority neighborhood. J Community Health Nurs. 2008;25(4):203-217.

2. Quinn DM, Chaudoir SR. Living with a concealable stigmatized identity: the impact of anticipated stigma, centrality, salience, and cultural stigma on psychological distress and health. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2009;97(4):634-651.

3. Bodnar-Deren S, Benn EKT, Balbierz A, Howell EA. Stigma and postpartum depression treatment acceptability among black and white women in the first six-months postpartum. Matern Child Health J. 2017;21(7):1457-1468.

4. Ward EC, Wiltshire JC, Detry MA, Brown RL. African American men and women’s attitude toward mental illness, perceptions of stigma, and preferred coping behaviors. Nurs Res. 2013;62(3):185-194.

5. Nelson T, Ernst SC, Tirado C, et al. Psychological distress and attitudes toward seeking professional psychological services among black women: the role of past mental health treatment. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. Published online February 8, 2021.

6. Taylor D, Richards D. Triple jeopardy: complexities of racism, sexism, and ageism on the experiences of mental health stigma among young Canadian black women of Caribbean descent. Front Sociol. 2019;4:43.

7. Edge D, MacKian SC. Ethnicity and mental health encounters in primary care: help-seeking and help-giving for perinatal depression among Black Caribbean women in the UK. Ethn Health. 2010;15(1):93-111.

8. Wyse R, Hwang W-T, Ahmed AA, et al. Diversity by race, ethnicity, and sex within the US psychiatry physician workforce. Acad Psychiatry. 2020;44(5):523-530.

9. Eack SM, Bahorik AL, Newhill CE, et al. Interviewer-perceived honesty as a mediator of racial disparities in the diagnosis of schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63(9):875-880.

10. Vahratian A, Blumberg SJ, Terlizzi EP, Schiller JS. Symptoms of anxiety or depressive disorder and use of mental health care among adults during the COVID-19 pandemic – United States, August 2020-February 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(13):490-494.

11. Greenwood BN, Hardeman RR, Huang L, Sojourner A. Physician-patient racial concordance and disparities in birthing mortality for newborns. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117(35):21194-21200.

12. Ozimek JA, Kilpatrick SJ. Maternal mortality in the twenty-first century. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2018;45(2):175-186.

13. Green TL, Zapata JY, Brown HW, Hagiwara N. Rethinking bias to achieve maternal health equity: changing organizations, not just individuals. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137(5):935-940.

14. Johnson Thornton RL, Powe NR, Roter D, Cooper LA. Patient-physician social concordance, medical visit communication and patients’ perceptions of health care quality. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;85(3):e201-e208. ❒