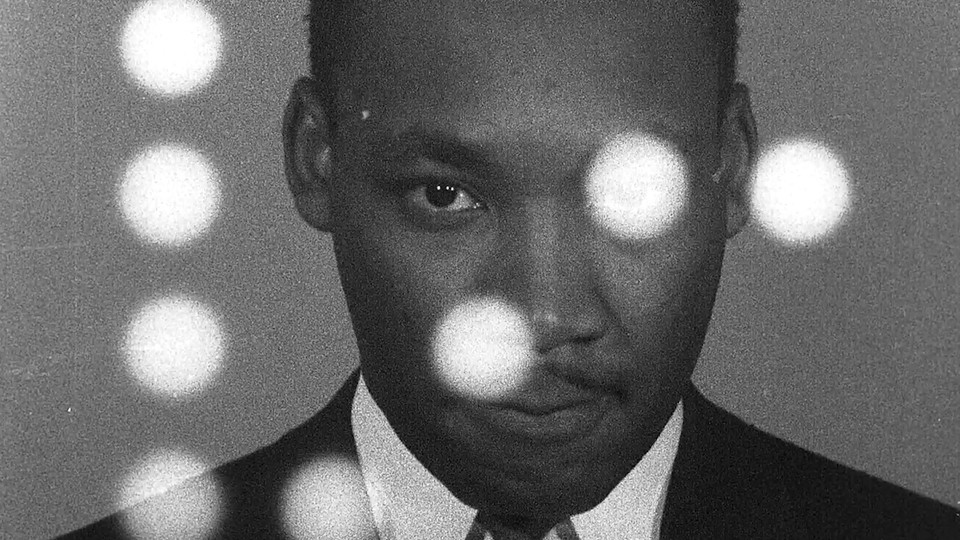

When the FBI Spied on MLK

The bureau’s surveillance of Martin Luther King Jr. reflects a paranoia about Black activism that’s foundational to American politics.

The Martin Luther King Jr. who is introduced to most American schoolchildren is a tragic hero—not just in a colloquial sense, but also in a mythological one. Greek tragedy is driven by characters just like the King described in textbooks. They’re brilliant and virtuous, yet doomed by a small error in judgment. King’s flaw, we are taught, was his idealism, which both made him a civil-rights hero and brought about his downfall. If we are to believe American textbooks, or even the speech President Ronald Reagan gave when he announced the establishment of a national holiday for King in 1987, we’d think this was the end of the story: The hero sacrificed his life for the dream of a color-blind justice, and the U.S. government has since been working to realize that vision.

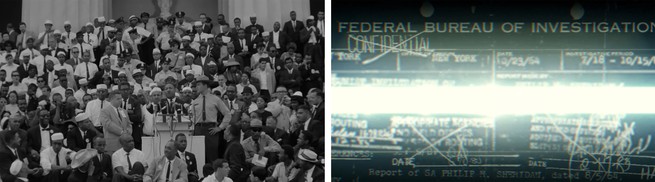

Consider King’s most famous quotes, especially the one that has come to define his legacy. “I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character,” King proclaimed at the March on Washington in 1963. But two days after he delivered that speech, the federal government wasn’t celebrating his words. On August 30, the head of the FBI’s domestic intelligence sent his colleagues an urgent memo about King: “We must mark him now as the most dangerous Negro in the future of this Nation.”

The extent to which the FBI spent the last years of King’s life attempting to neutralize that perceived threat is the subject of an insightful new documentary by the director Sam Pollard. MLK/FBI chronicles the bureau’s attempts to stifle the civil-rights movement through coordinated efforts to spy on King, with the hope of discrediting his righteous public image. With King, as with many Black activists since the beginning of the 20th century, the FBI’s surveillance wasn’t an isolated obsession. It was part of a long-running effort to keep Black Americans from acquiring institutional power, Pollard told me. “I know the history of Ida B. Wells. I understand the history of America after Reconstruction and how African Americans have struggled through the years of Jim Crow and segregation and lynching,” the director said. “I think one of the important things about this film is that it’s an opportunity not just for those of us who know this history, but for those who don’t, to come to grips with the complexity of American history.”

Pollard’s documentary places Sullivan’s memo about King in direct conversation with the virulent racism of J. Edgar Hoover, who often cautioned against the rise of a “Black Messiah.” Hoover, who had been the director of the agency when it was known as the “Bureau of Investigation,” became the head of the FBI when it was renamed in 1935. After ascending to that post, Hoover ran the bureau until his death in 1972, his time directing intelligence totaling an astonishing 48 years. MLK/FBI doesn’t just leave viewers to assume that Hoover’s long-running command of the FBI led to the targeting of King and other Black activists, including Ella Baker, Angela Davis, and Adam Clayton Powell Jr. The film traces exactly how the surveillance of King started, how it was conducted, and the effects it had on his life.

In doing so, MLK/FBI offers an important corrective to prevailing myths about King and his principles of nonviolent resistance, which were not, in fact, widely embraced. As my colleague Vann Newkirk wrote in 2018, “hostility toward the civil-rights movement turned into a cherry-picked celebration of the revolution’s victories over segregation and over easily caricatured, gap-toothed bigots in the South.” The reality was that opposition to King, and to the racial progress he symbolized, wasn’t restricted by region or by political affiliation. Democrats and Republicans alike had turned against King by his later years, especially after he voiced objection to the Vietnam War.

MLK/FBI also illustrates how the racist belief that Black activists are politically naive has long informed national-intelligence gathering. The film is based on a 1981 book by the historian David Garrow. (Garrow wrote an article for The Atlantic about the “reprocessing” of the FBI documents that detailed King’s surveillance, which made hundreds of pages newly available for public view in 2002.) The documentary shows that the FBI’s primary concern in the 1950s was the Communist Party. To the extent that Black leaders such as King initially caught the bureau’s attention, the documentary notes, it was because government officials believed that Black people as a population were easily susceptible to political manipulation. Well before the FBI invented a now-discontinued category called “Black Identity Extremism” to describe the Black Lives Matter movement in 2017, it formed COINTELPRO, a counterintelligence program meant to fight communism that instead targeted Black organizations as benign as bookstores. In 1958, Hoover suggested that there was a robust propaganda campaign afoot: “The Negro situation is also being exploited fully and continuously by communists on a national scale … so as to create unrest, dissension, and confusion in the minds of the American people.”

The documentary lays out the tangled chain of events that led to Attorney General Bobby Kennedy authorizing wiretaps of King, and what happened once the FBI had secured permission to do so. Despite Hoover’s anxieties about the potential arrival of a savior-like figure, the FBI director wasn’t originally trying to surveil King. The bureau was wiretapping a friend of King’s when investigators accidentally discovered that King was having an extramarital affair. Once the FBI stumbled on this detail, they got permission to surveil him. (Kennedy wasn’t aware of the bureau’s motive when he signed the orders.)

By the end of 1963, the bureau actively sought recordings of King having sex with his various girlfriends, in hopes of exposing him as a hypocrite and suppressing the civil-rights movement in the process. The FBI wasn’t just seeking to defame King using details from his private life. The bureau officials’ rush to cast aspersions on the reverend was both strategic and ideological. The documentary shows that they believed revealing King’s indiscretions would damage his—and the movement’s—claim to a moral high ground. “The thing that surprised me was how far the FBI would go to undercut Dr. King and his role in the movement,” Pollard said, referencing a letter the bureau sent to King’s home which insinuated that the only way he could avoid public shame was if he killed himself. “To me that was just going too far,” Pollard said.

Historians have called these specific tactics abuses of power, and MLK/FBI demonstrates just how meticulously the FBI worked to secure its intelligence about King. The documentary details how phones were tapped, and the lengths the FBI went to in order to bug King’s hotel rooms. These aren’t just procedural overreaches. Pollard’s film makes clear that the FBI’s surveillance of King—and, by extension, of other Black activists throughout U.S. history—reflects a paranoia that’s foundational to American politics and that didn’t end when King died.

It’s impossible to separate the FBI’s decades-long commitment to tracking Black activists from its relative failure to address the credible threats posed by white nationalists, including those that surfaced with last week’s deadly attack on the Capitol. The FBI surveilling King, and using dubious reasoning to do so, isn’t altogether shocking. For much of the country’s history, sabotaging Black rebellion—by any means necessary—has been integral to preserving white political power. The new, and still contested, development is finally accepting Black people as active participants in American democracy.