Tomorrow marks the one-year anniversary of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, a stunning and sudden shift in European politics that has triggered, above all else, a humanitarian crisis in Europe. According to the UN Refugee Agency, 7.8 million people have fled Ukraine in the last year, and while specific casualty figures are difficult to ascertain, one US general suggested there could have been 200,000 military casualties over the last twelve months, alongside 40,000 civilian deaths, demonstrating the scale of this conflict.

The war has also not been stagnant, with near-daily updates sent from correspondents in Ukraine to publications and news outlets around the world. This very magazine has published regular updates regarding the conflict, drawing from GlobalData’s database of facts and figures, as writers and commentators from all sectors try to understand and analyse the war in real-time.

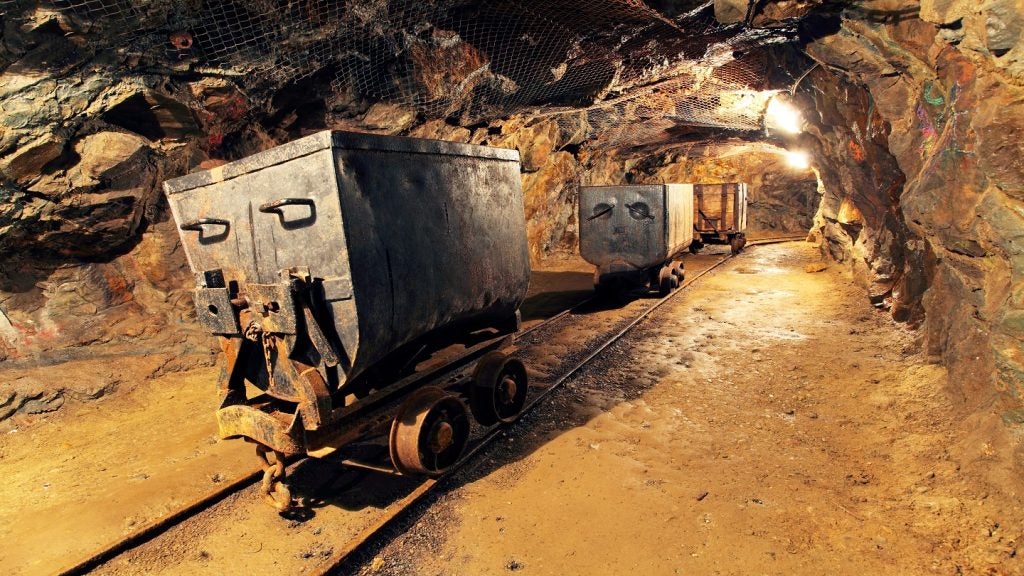

This is all to say that, despite the neatness of the approach of a one-year anniversary, drawing particular conclusions can be challenging as the situation continues to shift in real-time. Regardless, the war has left demonstrable fingerprints on the global mining industry of the war, with many of the world’s consumers now looking beyond Russia to satisfy their mineral wealth.

Yet, with such a massive industry as mining thrown into disarray by the war and the response of those beyond Russia, the main takeaway from the conflict, at least for mining, is one of confusion. With mineral prices disrupted and questions abound as to how the world will meet its unchanged appetite for commodities, the future is unclear, even one year after the invasion.

Commodities and productivity

Among the most dramatic consequences of the conflict, purely from a numerical perspective, are the declines in industrial production in Russia and Ukraine. According to GlobalData figures, coal production in these countries collapsed by 16.6% and 50.5% respectively, when looking at year-end production figures in 2022 versus year-end production figures in 2021.

See Also:

The decline in Ukrainian production is perhaps expected, considering the vast destruction sweeping across the country. The Kyiv School of Economics (KSE) announced in August 2022 that the total damage to infrastructure caused by the invasion had reached $113.5bn, and suggested that “almost $200bn” would be needed to repair destroyed assets.

How well do you really know your competitors?

Access the most comprehensive Company Profiles on the market, powered by GlobalData. Save hours of research. Gain competitive edge.

Thank you!

Your download email will arrive shortly

Not ready to buy yet? Download a free sample

We are confident about the unique quality of our Company Profiles. However, we want you to make the most beneficial decision for your business, so we offer a free sample that you can download by submitting the below form

By GlobalDataDamage to the “enterprises and industry” sectors alone reached $9.5bn, and these losses are likely to be compounded by the damage to Ukrainian infrastructure, which presents logistical challenges alongside ones purely associated with production declines. According to KSE, 311 bridges and 24,800km of roads destroyed were destroyed as of last August, a wave of destruction that adds further challenges to efficiently exporting Ukrainian coal.

The plight of Russian industry is more complex. On the one hand, the demands of the Russian war machine have created significant demand for the country’s industrial centres to meet; in March 2022, Russia’s industrial production increased by 4.5% over the previous month, as much of the country’s industry pivoted to more militarised activities.

Indeed, some Russian commodities are predicted to increase in value over the next three years. GlobalData predicts that the combined annual growth rate for Russian iron ore and gold, between 2023 and 2026, will increase by 3% and 0.9% respectively, and should these estimates come true, Russia will remain the third-largest gold producer in 2026, despite the rapidly-changing demands of its domestic industries.

However, this has had a negative effect on particular commodities, which have less obvious ties to the military sector. From the end of 2021 to the end of 2022, Russian domestic iron ore production fell by 16.3%, gold production fell by 11.6% and copper production fell by 11.5%, signs that the country’s long-term economic health could struggle, the longer its industries are tied up in military affairs.

Uncertainty surrounds investments in Russia

Beyond Russia and Ukraine, the combination of industrial destruction and reassignment has led to a shortage of many minerals, driving up the prices for a number of commodities. Between December 2022 and January 2023, the price of copper, iron ore, gold, and silver rose, suggesting low supply is driving prices for these minerals.

However, in the opposite direction, the prices of these commodities fell between the end of 2021 and the end of 2022. The price of thermal coal has behaved in the opposite manner, with a decline in price of 8.3% between December 2022 and January 2023, but a massive increase in price between the earlier year-end figures of 2021 and 2022. The average price of a tonne of thermal coal reached $357.9 by the end of 2022, more than double the price point of $136.9 at the end of 2021, perhaps suggesting that productivity of individual minerals has less of a macroeconomic impact than the general uncertainty and confusion triggered by the conflict.

A clearer outcome, however, has been the fate of Russian mines. While Russia entered 2022 optimistic about mineral expansion – just three weeks prior to the invasion, Russian backers drew up plans for two new copper mines with an investment of $15bn – the shifting nature of the country’s industrial and military sectors have reshaped international opinions.

For instance, in October, the London Bullion Market Association barred Norilsk Nickel from attending its annual metals conference in Lisbon, despite the Russian firm dominating its sector, providing 40% of the world’s palladium.

Similarly, foreign companies are withdrawing their influence in Russian mining. A piece in the Engineering and Mining Journal summed up Russia’s difficult position in relation to its import of mining equipment in particular. Across Russian open pit and underground mines, the share of use of imported equipment versus domestically-produced equipment increased from 54% in 2012 to 79.3% in 2019, and with many foreign companies withdrawing their support for Russian mining projects, this could leave as much as four-fifths of the Russian mining industry under-supplied.

Alternative partners for Russian miners

The obvious response to this reluctance to deal with Russia has been for overseas companies to find alternative sources of minerals. According to Eurostat, Russia supplied 55.6% of the EU’s hard coal imports in 2020, creating a massive gap in supply, and forcring European consumers to look elsewhere.

Not coincidentally, the second quarter of 2022 was astonishingly productive for Australian coal exports, and has driven optimism for the future of Australian coal. Figures from the Australian Government note that between 2021 and 2022, Australia exported 163 million tonnes of coal, and this is now expected to reach 183 million tonnes by 2023-24. The same report notes that the value of these exports has already jumped, from around $16bn (A$23bn) in 2020-21 to $47.3bn (A$68bn) in 2021-22, and this strong performance is expected to continue, with coal exports estimated to be worth $32.1bn (A$46bn) by 2023-24.

Yet for other commodities, alternatives are less obvious. Belgium is the world’s leading importer of Russian diamonds, importing 28.2 million carats in 2021, well ahead of second-placed UAE with 13.2 million. Russia produces around 30% of the world’s diamonds, and with such a strong link between the two countries, it is perhaps unsurprising that exports to Belgium have declined, but not evaporated. Figures from the National Bank of Belgium show that the value of monthly imports of diamonds from Russia to Belgium fell from around $107.6m (€100m) in January 2022, to a low of around $53.8m (€50m) in July 2022, through a sudden peak of nearly $430.2m (€400m) in the months between.

Unlike Russian fossil fuels, such as coal and oil, particular commodities such as diamonds are not so easily abandoned. Many have seen the conflict as an opportunity to reduce reliance on Russian fossil fuels, and invest more heavily in renewables, but there is no ethical, future-proof version of diamonds, or palladium. The world’s appetite for these particular minerals has gone unchanged through the war, and is unlikely to change once it has concluded.

Understandably, European countries have formed the stiffest resistance to Russian commodities, as a fellow European country in Ukraine is the subject of the Russian invasion, but other countries have fewer personal ties to the conflict, and so have felt able to continue to do business with Russia. For instance, figures from Resource World estimate that Asia-Pacific could have imported up to 30% of all Russian steel exports by the end of 2022, up from a high of 10% in previous years, and clearly establishing China as a new trade partner for Russian mineral exports.